Beyond Religion: What Does Chinese Culture Actually Advocate?

From creation myths to celestial hierarchies—decoding the remarkably hardcore humanism in Chinese culture

I believe that every sentient being who maintains self-awareness has, at some point in their long existence, paused before that ultimate question: "Where do I come from?"

It is precisely in the pursuit of "where I come from" that we glimpse the most hidden genetic code of a civilization. Every culture has its creation myth, and the reason behind that creation determines the fundamental character of that civilization.

Where "I" Come From

Why did our Pangu create heaven and earth? The reason isn't mysterious at all—in fact, it's remarkably mundane: he was bored. He woke up in that chaotic world, shaped like an egg, feeling stifled and uncomfortable. Simply wanting to stretch his limbs, he split open the heavens.

And then? To prevent heaven and earth from closing back together, he held them apart with his body until he died of exhaustion. After death, his eyes became the sun and moon, his breath became wind and clouds, his bones became mountains, and his blood became rivers. This is remarkably straightforward materialism: the world is made of matter, and the divine exhausted itself to create this world. After creating the world, Pangu disappeared—merged with it. He didn't stick around to be some lofty, finger-pointing "ruler."

How did the Western world come into being? God said "let there be light," and there was light. Why create humans? Because God is "good," and God simply wanted to create.

There's a massive logical trap here: once you accept that "God defines what is good because he is God," you've entered a closed loop. The Western logic goes: God is omniscient, omnipotent, and supremely good, so everything God does is right. If God brings disaster, it's not God's fault—humans have original sin, humans were disobedient.

Chinese logic is different: Pangu opened the heavens out of "physical need" (boredom), and Nüwa created humans out of "psychological need" (loneliness). Our gods are flesh and blood, with emotions and even limitations. This determined that we would never unconditionally kneel before an abstract "absolute truth."

Chinese People Don't Keep Idle Gods

Modern cultivation dramas often feel strange to us—why? Because the immortals in them do nothing but fall in love and obsess over bloodlines. This is very "un-Chinese."

Chinese attitudes toward gods and immortals are practical and hardcore—China doesn't keep idle gods.

Look at our mythological system: whether you're Nezha the child or the South Pole God of Longevity the elder, as long as you hold that position, you must work. If you have a post, you must produce results.

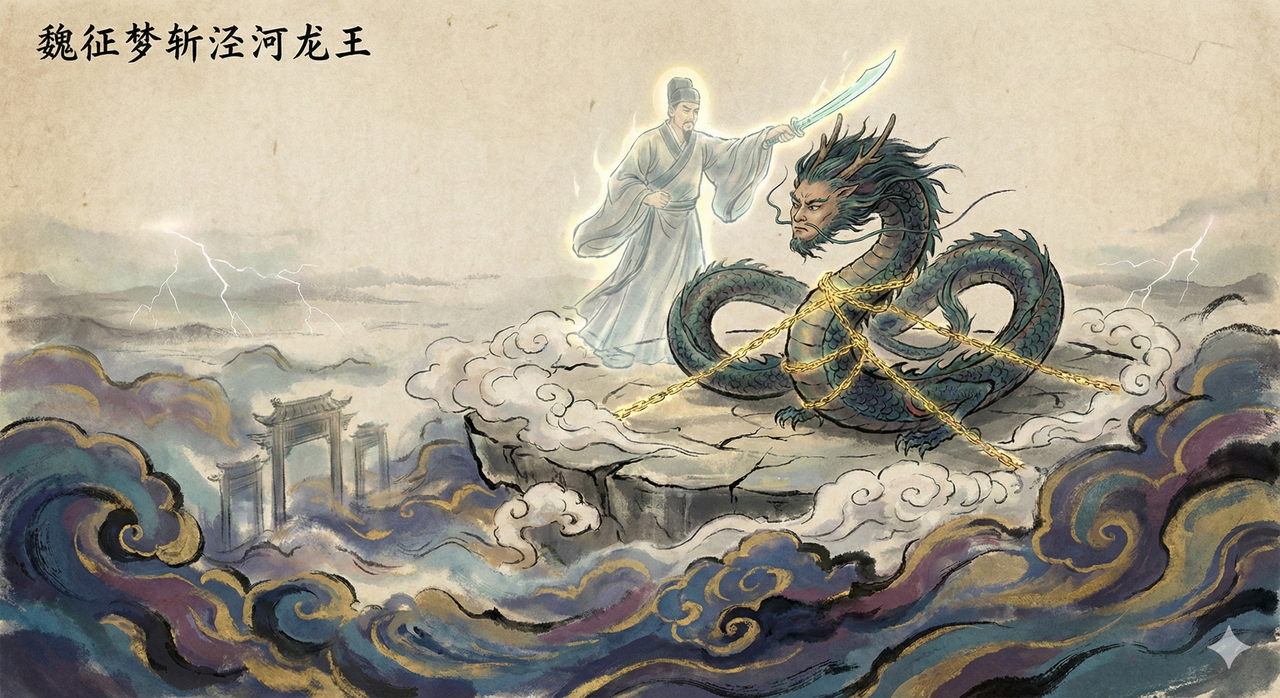

The most typical example is Wei Zheng's dream-slaying of the Dragon King of the Jing River in Journey to the West. Consider this carefully: Wei Zheng was a mortal (albeit a prime minister), and the Dragon King was an immortal. A mortal killing an immortal would be absolute blasphemy in Western mythology, but in our story, everyone considers it reasonable, legal, and proper.

Why? Because the Dragon King skimped on the rainfall, violating heavenly law.

This reveals a core logic of Chinese mythology: Above divine authority, there are still rules (the Dao/Law).

Immortals can't do whatever they want just because of noble blood—immortals are merely "civil servants" of the Heavenly Dao. If you perform poorly, occupy your position without contributing, or even throw a tantrum like Gonggong and damage Mount Buzhou (damaging infrastructure), you must be punished, even removed from your divine seat. Why were there later Water Virtue Star Lords and Fire Virtue Star Lords? That character "Virtue" (德) is key—the predecessor lacked virtue, so someone virtuous was brought in to manage.

In our conception, even the underworld keeps ledgers, and King Yama must follow the rules. When Sun Wukong wreaked havoc in the underworld, people see him as embodying a spirit of rebellion. But if King Yama dared to secretly alter the Book of Life and Death to extend his relatives' lives, in the common people's minds, that King Yama deserves to be beaten to death.

Not Worship, But Contract

Some say Chinese people have no faith because we worship everything, lacking devotion.

I say: nonsense—we're just too busy, one god simply isn't enough.

This relates to our agricultural model. Consider India or Nile civilizations—their farming was relatively "laid-back": the river floods, brings silt, scatter seeds, wait for the water to recede, harvest. They only needed to worship one river god.

China? We need intensive cultivation. Plowing, seed selection, fertilizing, irrigation, pest control, weather watching, disaster prevention... every step is life or death. With such a complex process, you expect one god to handle everything? Even working him to death wouldn't be enough.

So we must divide departments: the Earth God manages land, the Dragon King manages rain, the Medicine King manages illness—we even split the God of Wealth into Literary Wealth God, Military Wealth God, Orthodox Wealth God, and Windfall Wealth God.

Why so many Wealth Gods? The logic here is brilliant.

Think about it: if there were only one Wealth God. You're a loan shark, I run a small business. We both pray to him.

- For me to make money, I need to repay on time, so you can't collect high interest;

- For you to make money, you need me to fail to repay, so interest compounds.

Our interests conflict—who does the Wealth God protect?

So there must be division of labor, must be "non-compete agreements." You might even call it a market economy among immortals—whoever's effective gets my worship, whoever's capable gets more incense.

Heaven's Movement Is Vigorous; The Superior Person Strives Unceasingly

So, stripping away the religious garments, what does our culture actually advocate? The answer is just four characters: 人定胜天 (humanity can triumph over nature). Or put more gently—remarkably hardcore humanism.

In Western narratives, humans are "sheep" herded by a shepherd, and life's ultimate goal is redemption—returning to God's embrace (heaven). That's a path of "seeking outward, seeking upward"—you depend on grace. But in our cultural orientation, life's ultimate goal is "becoming a sage"—establishing virtue, establishing achievement, establishing words. This is a path of "seeking inward, putting down roots."

First, we don't place hope in a "savior."

Compare the flood myths and you'll understand.

Facing catastrophic floods, the West has "Noah's Ark"—God brings disaster, God selects the righteous, build a boat and flee. The logic: the world is broken, I'll find another place (or another batch of people) and start over.

China has Yu the Great controlling the waters—waters come, I'll tame them. Three times passing his home without entering, dredging channels, guiding water to the sea. The logic: the world is broken, I'll fix it.

This produces an extremely precious "constructive quality" in our culture. We don't await final judgment—we only believe in "the Foolish Old Man Moving Mountains" and "Jingwei Filling the Sea." Even if our strength is meager, we'll struggle to the end, rather than kneel and pray for the flood to recede.

Second, we advocate a kind of "contract spirit," not "blind obedience."

As mentioned earlier, our worship of gods comes with conditions. This sounds utilitarian, but actually reflects a high degree of equality consciousness in Chinese culture.

Heaven and earth are impartial, treating all things as straw dogs. Before the great natural laws (Heavenly Dao), gods and humans are equal.

When an immortal receives incense offerings, that's a "contract." If you take offerings but don't deliver, I dare to smash your temple, throw you in the river (local officials in history actually did this).

This orientation is embedded in our bones—Chinese people don't believe in evil. We respect authority, but the premise is authority must act humanely. If authority not only doesn't act humanely, then we respond with: "Are kings and generals born to their stations?"

Third, we pursue fulfillment in "this life," not the afterlife's other shore.

Look at our immortals—most were humans who "leveled up."

- Guan Yu was human, became a saint through loyalty and righteousness, then became a god;

- Mazu was human, became a sea goddess through protecting sailors;

- Lu Ban was human, Sun Simiao was human...

What does this advocate? It advocates—every ordinary person, as long as you excel in some field and benefit the people, you are divine.

We don't need an omniscient, omnipotent creator to define our value. In Chinese cultural orientation, the divine altar isn't some lofty forbidden ground, but the highest honor roll reserved for mortals who achieved great merit.

Most of the above is based on Daoist foundations. I must acknowledge Buddhism's influence on Chinese people is equally profound, but Buddhism is ultimately an "import." Fortune-telling as a service—monks don't handle it, but Daoist priests make a living from it.

Everyone Is Their Own Savior

So, what does our culture actually advocate?

It advocates: rather than gazing at the stars awaiting divine revelation, better to lower your head, repair the path beneath your feet, do well the work in your hands. In this civilization, everyone is their own savior.

Cultural Confidence Isn't Shouted

We don't need to flatter others' gods, nor reflect on why we're not like them. Being different is right.

"Where do we come from? What are our thoughts, superstitions, and myths really about?

What they are doesn't depend on how outsiders define us—it depends on ourselves...

Our culture can appear on the world stage in a way that doesn't flatter, doesn't pander, doesn't play victim, doesn't self-criticize—clear, dignified, and beautiful."

Afterword

The original intention of this series is to clarify some foundational logic of metaphysics, helping everyone understand the culture behind "metaphysics"—our own culture.

The core of our culture is that phrase: "Heaven's movement is vigorous; the superior person strives unceasingly." Everyone is their own savior.

The textual material was collected and reorganized from online sources, not my original creation—I'm merely a curator of materials. If any infringement, my apologies.

All images by artist: Gemini3 Pro

Feel free to repost, no commercial use.